Dec 23, 2025

We spend years developing our skills and judgment, but rarely examine the inner voice that shapes how we use them. Inspired by the Saboteur Assessment, this piece looks at how that critic operates and what can change when you start noticing it instead of following it.

I recently had a session with a top executive coach. She asked me to do a short self-assessment, the Saboteur Assessment. I didn’t expect much from it. And then, to my own surprise, I loved it.

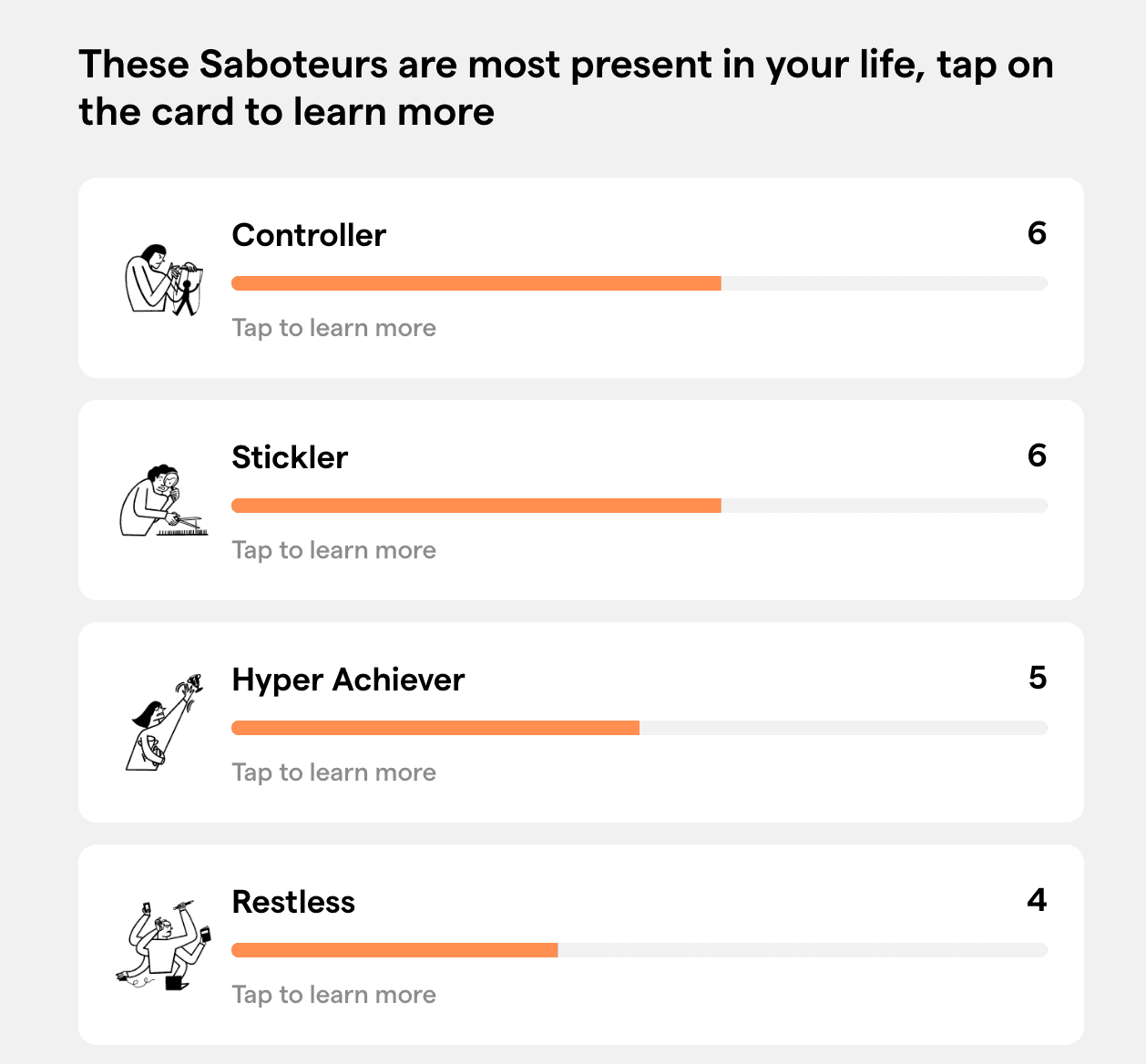

Test results show archetypes of the inner critic.

This was not just another online self-help test. The Saboteur Assessment, part of the Positive Intelligence framework, measures mental fitness by estimating the balance between the “Sage”, the constructive and adaptive mind, and the “Saboteur”, the patterns of thinking that work against us under stress. The model is based on the New York Times bestseller Positive Intelligence by Shirzad Chamine, who has trained faculty at Stanford and Yale business schools.

To be clear, the assessment was not useful because it was comforting. Quite the opposite. It gave language to something most of us experience every day and rarely stop to examine: the way our own mind can quietly work against us.

You know the moments. You leave a meeting that went well, yet your mind fixates on one sentence you could have phrased better. You wake up at night worrying about a decision you already made. You delay a difficult conversation because it doesn’t feel like the right time. Or you reach a meaningful milestone and almost immediately move the goalposts.

Your mind is your best friend. It helps you plan, anticipate, protect, and perform. But it can also be your worst enemy.

This idea of an inner critic is well established in psychology. Often described as inner speech, covert self-talk, or internal monologue, it refers to the ongoing verbal commentary we carry inside our heads. Research suggests that this internal dialogue plays a central role in how we regulate our thoughts, emotions, and behaviour across both childhood and adulthood. Psychologists Charles Fernyhough and Peter Alderson-Day, for example, argue that inner speech helps us plan, reflect, and problem-solve, but can also reinforce self-criticism and rumination when it turns repetitive or evaluative rather than constructive.

The Judge

How do you become aware of the critic that lives inside you? The test introduces the concept of the Judge, the master saboteur we all carry. The Judge replays mistakes long after they matter, warns obsessively about future risks, and keeps pointing out what is wrong with you, with others, or with your life.

What makes the Judge so powerful is that it rarely sounds harsh. It sounds reasonable. It disguises itself as realism, responsibility, or high standards. Especially in leadership roles, it can feel like competence. Over time, though, it quietly drains energy, increases stress, and narrows perspective.

Once active, the Judge invites other patterns. Avoidance, control, overachievement, perfectionism, constant busyness, people-pleasing, or relentless vigilance. These are not character flaws. They are learned survival strategies — automatic ways the mind tries to keep us safe, valued, or in control.

The value of the assessment is not in fixing yourself. It is in noticing. When a thought is named, it loses some of its authority. You begin to recognise when the Judge is speaking, instead of assuming every critical voice is true or useful.

For me, the shift was subtle but powerful. I stopped asking what was wrong with me and started observing how my mind reacts under pressure. That small change creates space. And in that space, choice becomes possible.

The assessment is not therapy. It is a mirror. Leadership, growth, and a meaningful life rarely begin with doing more. They begin with seeing more clearly.

Sometimes, one simple test is enough to change the conversation inside your head. You can do the 10-minute test for free here.

Other top stories to read next

Stay on the pulse, catch the signals

Subscribe to Listeds Leadership Intelligence Platform:

leader and company database access

email alerts

career, boards and interim opportunities

All Listeds Newsletters

Our leadership, strategy, and lifestyle essentials.

Subscribe once and get all three of our flagship newsletters: Best of the Week, Pulse and Weekend.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy